Jason Priem talks about altmetrics, total impact, and decoupled journals

Jason Priem from UNC Chapel Hill's library/info department gave a he's giving it as I type this -- welcome to the talk liveblog.

One common theme throughout the presentation is that scholarly communication has always been limited by the best-available technology. Writing individual letters by hand made sense when we didn't have the printing press - at least it let us get our ideas out to others. Printing centralized journals made sense when we didn't have the internet - we could reach far more people this way, and that was worth the constraints of large-scale centralization and all its accompanying restrictions of limited print space and needing to wait many months or even years to hear about scientific progress. But now that we do have the internet, we no longer need industrial-scale replication in order to reach a wide audience - and so the next publishing revolution will promote a diversity of outputs.

Research has several different types (or stages) of output; the web changes them all.

- Data - raw output. Logs. Pictures. Probe data. Satellite dumps.

- Analysis - what you do to the data. As computerized tools make their way deeper into the research world, it becomes easier to track the actions you took - the commands you told your statistics package to add, the codes you assigned to this portion of the interview - and suddenly it becomes possible, even easy (technologically, if not legally/culturally) to release this to the world as well.

- Stories - once we've analyzed the data and learned something from it, we tell the tales of our journeys in knowledge, often via journal articles.

- Conversations - how we talk with colleagues about them. The web has been transforming how we have conversations - witness the proliferation of reference managers (zotero, mendeley), blogs (wordpress, blogger), social bookmarking, and social networking software. Some of these conversations are, and could be - gasp - scholarly.

Jason discussed the example of using Twitter for research. He no longer reads the table of contents of many journals - he simply follows a hundred or so other researchers and reads the papers they tweet about. More and more researchers are beginning to use Twitter as a scholarly tool -- and cooler yet, there's no significant differences in adoption or usage between disciplines or stage of career. (See "Prevalence and use of Twitter among scholars" here.) This means English grad students and tenured chemistry faculty were equally likely to use Twitter intensively for research. I can't help but wonder if this sort of thing might lead to interdisciplinary conversations that may not previously have taken hold.

(A better version of the graph can be viewed here.)

There are several different types of scholarly tweets. "Primary" tweet-citations ("citwations") link directly to a scholarly paper, but far more common are secondary citations -- tweets referring to blog posts that in turn refer to scholarly papers. This is due in part to questions of access; researchers are hesitant to link to papers behind a paywall their colleagues (and followers) may not have access to, but they know that everyone can read a blog post.

This isn't an entirely new idea -- it's just that we've recently acquired the tools to actually do it well. The Science Citation Index was created by Garfield in 1961. The big idea was to use crowdsourcing (remember, this was 1961, long before "crowdsourcing" was a buzzword) to fill the role formerly held by individual expert judges. Instead of asking one person how "good" an article was, why not just see what researchers use -- what data do they mine and cite? The more folks use it, the better it's likely to be. In other words, Garfield invented Google PageRank decades before the internet took hold.

So why does Google PageRank make a lot more sense to us than "scholarly citation indexes?" Well, a citation index has limitations. It only deals with academic people using scholarly articles as resources for a single use - writing other scholarly articles. And of course, there are a lot more people than researchers. And even researchers do a lot more with articles than write other articles about them. There's this entire universe of usage we aren't capturing or counting.

For instance, I'm an engineering education researcher(-in-training); my work is designed to be read by - and impact the work of - people who do not publish scholarly articles. Engineers. Hackers. As a grad student who hasn't yet been primary author on a peer-reviewed journal paper, my citation impact is zero - but my impact is arguably nonzero. My work on teaching open source has reached dozens of faculty, touched hundreds of students, been read by thousands of hackers, been blogged, tweeted and dented, found its way into classes being taught, textbooks being written, conference talks...

When I stand up several years from now and present my portfolio and defend my dissertation, I want this work to count. When I look for a faculty position (if I do), I want to go to a school that values the sort of impact I care about -- and I want a way to show them what that is and how they can evaluate me on it. That's the idea behind Altmetrics, and I'm sold. I think I'll pitch Shannon on letting me do my end-of-term project on publicly instrumenting my scholarly life to gather and display altmetrics and getting all my old research open-access, so I'll be clear to "do it right" going forward.

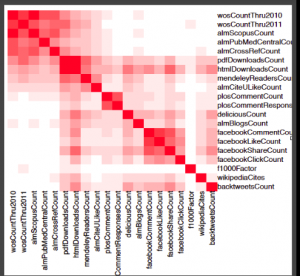

Altmetrics impact is mostly orthogonal to traditional citation impact, so if you care about it, it's important to make sure you gather it because it'll be invisible in your portfolio otherwise. There's a great slide showing the correlation of one type of citation to the other (the image below, grabbed from Jason's slides). You can see that html and pdf downloads correlate with everything, that social media has its own cluster of correlation in the lower right, and that traditional scholarly citations have their cluster in the upper left. But the picture is clear; relying on scholarly citations alone misses a giant portion of the real impact that your work is having.

You can also look at large bundles of altmetrics data and see the different "types" of articles -- there are, of course, a few (3%) that become popular with all walks of people, scholarly and nonscholarly, as well as many articles (a bit over 50%) that aren't popular with anyone at all. But there are articles that do well with traditional citation metrics but aren't "popular" on the internet - canonical papers, methods papers, things researchers cite as foundational work. And there are articles people share on scholarly networks like Mendeley but don't cite in their own papers - what do we make of those? (There are more of these than we may think. 80% of the articles in PLoS are in at least one researcher's Mendeley library.) How about articles with a high Mendeley ranking but no Facebook posts -- are those the ones of interest to a specialized population but nobody else?

As for gaming the system -- yes, every system can be gamed, including our existing citation system. But the more data you have, the easier it is to spot gaming by eye or by automation -- it's a classic instance of "more eyeballs make bugs shallow," - the eyeballs need sufficient data on the "bugs" to make them "shallow."

All right. We've talked about a different sort of citation and impact tracking system, but we're still applying those trackers to conventional outputs - papers in scholarly journals. What if we applied web tools to those as well, and started publishing with the best tools the 21st century had to offer, instead of the best tools the 17th century had?

Let's talk feature set. Anything that tries to supplement or replace journals will have to have feature parity on four fronts: certification ("yes, this research is high-quality"), dissemination (getting research out there), archiving (keeping it findable in perpetuity), and registration (are you who you say you are?).

Of these four, existing simple web tools do a far better job of everything except certification. (Heck, mailing lists do a better job.) Certification is still vital, though; it's why we have peer review. We want high-quality research, and high-quality anything requires careful scrutiny, feedback, and filtering.

Jason's point was that this filtering doesn't need to be done in a centralized place by a single group of people. And he launched into a description that looked surprisingly similar to the discussions on content stamping we were having at OLPC some years back.

And it's already being done. "My twitter feed is like a private journal," Jason said. "The people who care about my work - the... you know, four people who care about my work - they follow me on twitter, and they'll read everything I write, and that's peer review." More large-scale examples are F1000 and ArXiV, and there are others.

Like any good hacker, Jason had a call-to-action in his talk. Want to try things out for yourself? Check out Total-impact, a web tool that lets people put in collections of (scholarly or nonscholarly) materials and get a wide range of citation stats on them. I wonder how well the opensource.com/education articles play in the semi-scholarly spaces... probably not that well (since that's not the intended audience), but we could be surprised.