Full talk transcript: "Psst: wanna eavesdrop on my research?"

Here's the transcript of the seminar "Psst: wanna eavesdrop on my research?" hence the disciplinary focus). I've edited in some context for readers who weren't there, and anonymized audience comments (except Jake Wheadon's interview -- thanks, Jake!) and the transcript cuts out before the last 2 audience questions, but otherwise this is what happened; click on any slide's photo to enlarge it.

TRANSCRIPT START

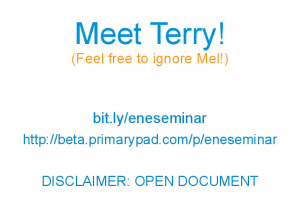

This will be a slightly strange seminar; I've had at least half a dozen people e-mail me and say they can’t be here but would like to catch up later on. So we’re interacting here and it's being recorded by Boilercast and transcribed by Terry over there.

The title is long and fancy and we're going to ignore that.

I'm Mel. I think you all know me. I'm a Ph.D. student here in engineering education and one of the things I do is qualitative research, because it’s fun. I also come from the hacker world, the open source, open content world where there's this radical transparency culture that defaults to open and share everything about what they’re doing.

This is Terry. She is a CART provider and the one responsible for typing super, super fast on our shared transcript document. The URL for the live transcript is on the slide for those of you who are following along on Boilercast. You should know that all of the recordings and the documentation and so forth we're producing in the seminar will be open data. That means a couple of things.

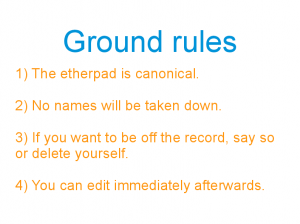

First of all, the document that Terry is transcribing in is a collaborative text editor and you can type and annotate and fix spelling or whatever you want. It will be the canonical record of our discussion. The second is, as we’re recording this, no names will be taken down. So it's not going to say I said this and you said that and this person said that other thing. It's just going to be “person in room” said words. If you want to be off the record, if you don't want Terry to type down what you're saying, say that before you speak and she will stop typing for a moment, or if you see something in the document you can go and delete the stuff you said if you don't want it on the record. The document will be available for editing right after the seminar as well. I probably won't read and post the final version until sometime after dinner. So you can also take out stuff you said afterward if you don't want to be captured here. The ground rules are also in the document.

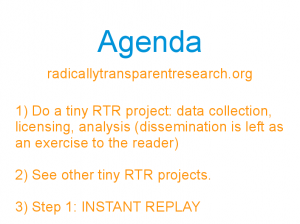

This is what we're going to be doing today. It's a bit of an adventure. I've been playing are something called radically transparent research. There's a website and it's out of date and once I finish my papers I'll fix it. What radically transparent research refers to is this: what if we did engineering education research, or any kind of qualitative research, as if it were an open project? Make the data open, the analysis open in terms of both being publicly available and open to anyone who wants to participate, and not having a delineation saying “these are the official people” on the project and “these are not.”

What would it look like if we defaulted to open instead of defaulting to closed? So what we're going to do is we're going to do a little RTR -- radically transparent research -- project right here in this room. We’ll be collecting data, going through the licensing process, seeing what analysis looks like, and dissemination -- we’ll get back to that. We'll see a few examples of other projects that RTR is being used in and then we're going to loop back and and do an instant replay of “okay what the heck just happened?” I'm hoping as we go through the steps they'll seem fairly logical, but then when we go back and compare them to the normal way of doing qualitative research they'll start seeming really weird and the implications of the pieces lining up will start piling and piling and piling.

(Note: this was a 45-minute talk, so for the sanity of feed readers, I'm going to say "click to read more" here.)

So that's enough talking from me. First thing we need to do is collect data. So if I can have my audience volunteer Jake, come up here... we're just going to do an informal quick mini interview, I asked him about this 10 minutes ago so there’s been no prep. Jake, you told me that you've been reading the work of a researcher called Saraswathy, and I was curious what kinds of ideas you've been seeing and why you were so excited about this person.

JAKE: As you already know, and some people, know my research is a lot about entrepreneurship and how to teach entrepreneurship and whether or not entrepreneurship is useful for engineering students and in engineering education and why and and where does engineering and entrepreneurship mix. It was really exciting reading this book by Sara Sarasvathy because she is all about entrepreneurship but gets really heavy into philosophy and the types of things we've talked about in history and philosophy and design cognition and learning, especially the Herbert Simon’s work about the -- gosh just lost it -- like, um the artificial science

MEL: Okay.

JAKE: You know not artificial as in fake but having to do with artifacts. That's the kinds of logic and problem solving skills that come out of that philosophy are really relevant to entrepreneurs. But I got excited about it because I know they're really relevant to engineers as well based on the things we've done in our classes. So it's been really cool to see how she applies that to entrepreneurship and I could see if we were trying to teach our students in engineering those types of logic and those ways of thinking, that would be really useful in both fields. There's kind of a common philosophical foundation for both of those fields if we line them up right .

MEL: For the fields of engineering...

JAKE: Of engineering and entrepreneurship.

MEL: Yes, and the common philosophical foundation is...?

JAKE: Mostly like the theoretical work of Simon around that, you know, artificial science and Saraswathy goes into detail on the way she sees that logic working. She calls it effectual logic as being different from other types of logic. It's those kinds of problem solving skills she found in her research that entrepreneurs use as they try to solve entrepreneurial problems.

TEXT COMMENTARY FROM AUDIENCE: Pointing to what stands out - connection - connecting one body of work to another - exciting to see connections

MEL: Cool. I'm going to pause here for a moment. When we go through this in a second we'll talk about how this was similar to and different from a normal interview, but for right now, roll with me here. I'm going to need you for a couple more minutes.

JAKE: That’s okay.

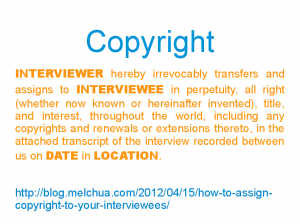

MEL: License data. So right now we have collected this interview data. The transcript is already there. It doesn't belong to anyone per se, so I need to specifically give Jake the copyright for it. There's a nice little template here to do that.

I, Mel Chua, hereby irrevocably transfer to Jake in perpetuity the transcript of the thing that we just said here on the 18th of April in the engineering education seminar. Done. What that does is it legally gives Jake all the rights to this transcript. So from a research subject standpoint, he now has all the power for everything about the data. I can't use the data for my research until he says I can.

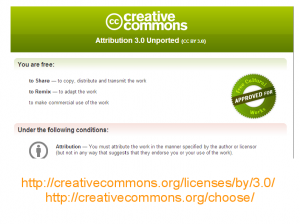

So the next thing is then you can ask your subject, okay, now that you own that transcript, we're going to try and come up with an open licensed version of it by applying a creative commons license. These kinds of licenses can grant certain kinds of rights. You can give people the right to share your work, remix your work but there's always an attribution clause that requires that if you use my stuff you must cite me. So there are no worries about people scooping me and running away because they have to point back to my dataset in any work they do. So Jake, what I'd like you to do is if you can come over to-- we have your transcript up on the screen here...

JAKE: Okay .

MEL: I'd like you to look over it a bit and see if there's anything you would like to take out or correct.

JAKE: I mean do you want me to go through this and do it?

MEL: Yes.

JAKE: I don't know off the top of my head I would-- am I able to do this right here? There's no way that our transcriber would guess the spelling of the name [Saraswathy] from me saying it... (Jake corrects some typos)

MEL: We're correcting the spelling of the name.

JAKE: Yeah, um, I mean I can do a couple more of those if that is helpful. I don't know what kinds of things. There's nothing in here that I'm against having shared if that's where we're going

MEL: Yeah, pretty much. And is there, as you look through this are there any patterns or things that come to mind of “oh, I said that?”

JAKE: I-- probably just I mean the big theme is that is connection, you know, trying to find, and I guess that's a big theme of what I'm trying to do anyway is connect this body of stuff to this body of stuff and get them together. I guess the part that excites me about the things I'm reading is when it is helping to draw those connections that I'm trying to find.

MEL: Thanks Jake.

JAKE: Okay. I'm safe to go home?

MEL: Yeah, cool. [Audience laughter] So this was obviously a really, really short on-the-spot interview. We couldn't get very deeply into things. There were a couple of interesting things that happened. First of all the conversation that we've been having is also in the transcript, so backtracking a little bit...

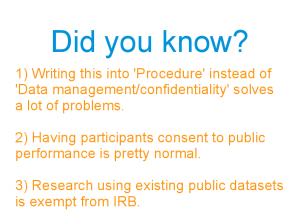

How would this work with IRB? Before doing any of this interview stuff, hypothetically, I would have gone through the IRB process, which has all these things about anonymity and confidentiality. There are some things you should know about this part.

The first one is that it just becomes part of the procedure that you're asking your participant to consent to. If you were going to have a study where you said “I'd like my participants to get up on stage and give a talk” or “I'd like them to stand in a public place and ask them about whether they like chocolate or vanilla” -- that's normal in the research world. As long as people know what they're doing and consent to it, that's fine. Same with IRB for this. As long as your IRB form makes it clear that you tell people it's a public performance and the data is going into an open data set and they’ll have a chance to check it over, IRB is cool with that. Don’t put it in the “Data Management and Confidentiality” part because that sets you up for confusion. The cool thing is that once you have the open data set, you or other people can use it because it's now public and anyone can access it. You're the only person that has to go through that one hurdle and then other people can benefit from your work.

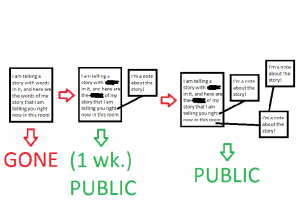

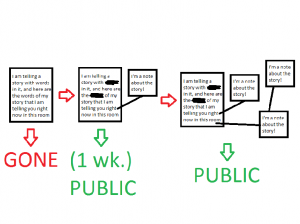

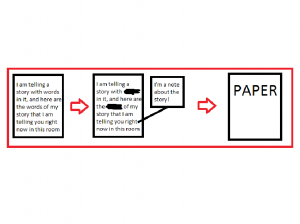

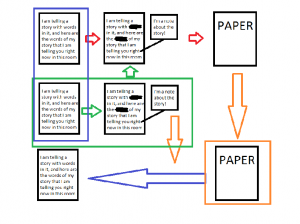

This is the process of what happens with the data. The first thing we have is the raw transcript on the left side of this diagram, that’s the transcript that we generated through our conversation. Then moving along to the middle of the diagram, we have the version where we’ve edited a couple of things. For instance, if you had an interview subject that said “Oh geez, I didn't mean to say that, I don't want this part public,” they can change names in the text, or use pseudonyms, or just say “a student in my class over the past 10 years” instead of “Bob Smith” or whatever.

Now the original document is gone forever with all the things the subject wanted to edit out, and now we have the edited document, the one we generated in this room when Jake went through it. There's a one week time-out before it goes public, so people have more of a comfort zone and aren’t put on the spot to edit everything perfectly right away, in case they realize something when they walk out of the room or wake up the next morning, and then after the one-week timeout we have a public dataset.

An interesting thing is that we also have a little bit of commentary and meta-analysis already in the dataset because we were looking at it right after it was generated. There was some indigenous coding going on -- “oh, I talked a lot about connections.” That might be a theme in the data, then. And then going on to the right side of this picture, now that this is a public, open dataset that's been open-licensed, our subsequent analysis and work and commentary on it is also public and open and available to others to see.

The third step is analyzing data. There is a URL here on the slide and if you open up the other link you'll see-- give me a moment to pull it up here-- another transcript. So this is an example of another RTR project. A couple of us -- Hadi and Robin and Junaid are here -- have been playing with stories of faculty and STEM professionals that are considered changemakers in their field. This is an example of what collaborative analysis can start to look like. The tools don't really matter. The coding approach doesn't really matter. It was just the idea that you can go through and see what different people have said, and... actually if you go to this website right now you're also going to be able to highlight things, add notes, add comments and see who said what, who noticed what. So feel free to play around in any of this in the background instead of listening to me talk. That's completely fine.

The other interesting thing about the analysis is as I mentioned earlier we've already started this process. A lot of those steps start blending together. Gathering data is kind of the same as analyzing it. You start analyzing data while you collect it. Analyzing the data is kind of like disseminating it. I’m getting ahead of myself.

Step four, disseminate. One of the interesting things about this -- if you noticed one of my earlier slides said we were not going to do dissemination...

Good, you caught it! Because with RTR, the dissemination step...

...is the same as the analysis step which is kind of the same as the data gathering step. What we're trying to disseminate is the process of analysis itself because there's been all this research showing that change, especially educational change, doesn't happen by spewing journal papers out to people. It changes through one-to-one contact, through dialogue, through participation. The people that are most changed by research project are the ones participating in it. Therefore, if you want more people to change as a result of your research project, get them to participate in your research project. Don't just hand them papers after the fact.

TEXT COMMENTARY FROM AUDIENCE: so this is where mentoring - or partnership, really - is critical; access to ongoing projects - or conversations - as critical.

MEL: I'm going to go to back to slide 5. What I want to do is loop back through the process of what we've just done and compare this to what it would normally look like doing that step in a conventional method.

Data collection. Usually it would be me and a subject who I have selected, in a room by ourselves, tape recorded or somehow captured. I might be taking notes. The conversation we would have would be pretty much the same. There is nothing that really changes about the interview procedure. I ask the same kinds of questions. They give the same kinds of responses.

Licensing. That was different. We usually don't do that in a project. Maybe we should. We don't really usually need to worry about it because our data goes off to another world. If you read the consent forms you have subjects sign, they sound like this: “I'm going to take 2 hours of your valuable time. We're going to have a conversation, and then the artifact of that conversation will come back into a black box locked in the bottom of the sea where it will never see the light of day again.” So you just spent two hours of your time for what? I mean, it was nice to have that conversation. You're contributing to knowledge. But there's nothing really that subjects can take away from it and bring to people. They can’t say “I just had a really cool conversation with that person over there about STEM education in urban schools and how third grade girls like Legos” -- well, they can, but they have nothing to show people. Licensing the data is a step that empowers participants to control and take that data and use it for their own ends and means.

The next couple of slides were the things we went through with the copyright and licensing. Because we don't usually license or assign copyright of interviews it's really unclear who owns the right to that data, so ten years from now it's difficult to go back and say “that was a really cool study, can I use your data?” We usually don't do that because we know it's hard. But if we take care of that up front and it's easy, maybe we'll do it more often.

IRB. The IRB is not that different. All we're doing is adding a little thing at the top that says that as part of this interview the participants understand they're consenting to be part of almost like an oral history database. Their story is going to go here and other people will see it, not just me.

This puts certain restrictions on the things you can talk about. You can't do radically transparent research where people are fully identified with their names and institutions on topics like “what makes people really angry when they think about how tenure and promotion are affecting the lives of assistant professors?” You can't tackle that research question witih RTR. You also probably can't interview 5 year olds and prisoners. There are research questions this doesn't work for.

But who do we talk to most often in engineering education research? Adults, professional engineers or students, teachers, faculty members, people that have really interesting stories and actually really like sharing their stories and would like to share the stories more and would really like to see the stories of other people. One of the most interesting things I’ve found while doing RTR with my own projects is that interview subjects say “oh, does that mean that everyone else you're talking to, I can go see their stuff also? I'm going to go do that. And the next time you see this, person can you ask them this question?” They start getting into this sort of conversation. The data starts talking to itself, literally.

Fom an IRB perspective, all you’re doing is adding “public performance” to your participant procedure and it’s not terrifying at all.

Here’s the RTR process of data evolving from raw into finished forms. We do this already. We get our raw data, maybe we edit it because the undergraduate we hired to transcribe didn't get this part, or the audio is unclear, or something. The data gets changed and analyzed.

We do our analysis. Right now we usually analyze in a vacuum or maybe sometimes with a friend we bribe with pizza. If you are doing RTR, you might still be analyzing by yourself; it’s not a magic guarantee people will show up and help with your project. But they can! They might! Even if you are doing RTR, you can still analyze with any theory you want, any coding scheme you want, any tools you want, nothing about that has changed.

In non-RTR research, dissemination is a separate thing. “Now that I've done all this stuff by myself, I'm going to show you what it looks like on a shiny journal paper.”

And there’s the cat. RTR has adorable animals. Very important. Just kidding.

Dissemination again. What I'm trying to show is that the process we just went through is not too far off from our current research practices. There's just some very small minor changes in what we've done in the process, but it started opening up a couple of very interesting possibilities. They may not go anywhere, but they could go somewhere that we've just not imagined before.

All right, going on.

Here we have the way we work with data now. It's bundled together, all our data and our analysis and our final output for dissemination are all in this giant big block. They come as one, and I, the solo researcher, or maybe the research team, I do all three of these by myself. What else could it look like?

What if we decoupled these things? What if data sets were things we had, separate from publications? What if at the end of my dissertation I was able to say I wrote my thesis, defended it, I’m a PhD now -- hopefully that will happen -- and I've generated two journal papers from it, which is awesome, and those papers have been cited by 3 other people, which is also awesome.

But in the meantime 3 other people have used my data set for two different projects. So I actually have citations of my dataset, and some projects have used my analysis and are citing my analysis, and so I’m getting more citations because I’m sharing more things. People are able to use my stuff more and I'm able to get more credit for other people using my work. We’re decoupling these things.

Now, maybe someone else interviews other people working on entrepreneurship and engineering education, and they open up that data set, and now there’s more data I can analyze without having to go out and do that interview. So data sets can get shared. Analyze can get shared. Output can get shared. So this makes the process more granular. There's no reason why all of these three things of data analysis and final output need to be bundled as tightly as they are. We’re just starting to separate them.

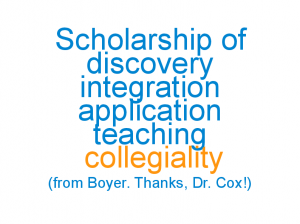

When I was talking with Dr. Cox about that last slide, or an earlier version of it, she brought up Boyer’s scholarships of discovery, integration, application and teaching. She said this is something really interesting. This kind of tumble, this sort of mess is almost a different thing. It's almost like a scholarship of collegiality, where you're making people more able to do the stuff they want to do.

It's not just researchers. Remember the participants are taking home the transcripts. They may share them with other people and look at things from the other participants. So there's some activity going on in that field also with people who would maybe normally not be involved in the research process who would not have been able to see behind the scenes of the research projects. Now they have a chance. Maybe you interview an high school teacher, and they share the interview with their class, and there's a student there that gets interested and as a result of being able to see behind the scenes they end up doing something in engineering education. Who knows?

It's a long shot but we'll never know unless we open up the possibilities. It's really cool when people surprise you.

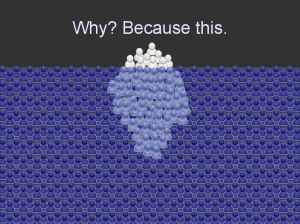

Why is this important? This is a picture of an iceberg. This is us, the white bit at the top. This is what we can see. There's this grey part, the ice under the water, the mass of people who kind of participate in research. Maybe these are the people that are outside Purdue that we correspond with. Maybe these are some of the subjects we’ve talked with and they're kind of participating but they're under the surface of the water and nobody else can see them.

Then there's this mass of people here who don't know what's going on. How can you participate in a conversation if you've never heard it before? We have all sorts of interesting interactions at Purdue in these rooms, in these hallways and then we go outside... I'll go and talk to friends from college or high school and they have no idea what I'm talking about and don't know why I'm doing what I'm doing because -- what does that even look like? We’re trying to bring more things up to the surface -- we don't have a Discovery Channel show yet -- but we can show people this is what we do. This is how it's cool. This is how it affects others.

When you expose your process to people, you give them the background context as to why you’re doing what you’re doing, and how. This picture is of little kids learning how to cook. They're still at the point where they need cookbooks guiding them through step by step. They don’t have context yet.

And then there's Iron Chef. The people in this room are closer to this side of the spectrum than the little-kid side. We can plunge into data and into experiences and we’ll instantly be thinking of different theories, citations, projects, everything. How did we learn that? We came to grad school to take classes in history and philosophy, and in grad school we see other people make those kinds of connections. Before grad school, most of us didn’t get to see that. So this is a way to put ourselves in a fishbowl and let other people see us in this space.

TEXT COMMENTARY FROM AUDIENCE: provocative insight - gets into a power differential that is quite "powerful" - the researcher/subject relationship is different in this scenario - both are researcher/partiicpant - it doesn't necessarily enable someone to talk about something sensitive - but it changes ideas about who gets to talk, who gets to have an opinion, laying yourself open to putting yourself in the "subject" role.

MEL: And when you get the little kids and the Iron Chefs into the same room watching each other cook, you immediately get hit by the fact that the same thing can look very different to different people. We know this already, but there’s a difference between knowing it and seeing it in front of us. Having that combination of novices and experts, and lurkers and doers, and letting people jump from looking into participation whenever they want, allows people -- including us -- to flip back and forth between all these different viewpoints. You start seeing “Ah, this is what a novice thinks of this, and it’s confusing to them, so maybe I should clarify it.” You start thinking “Oh, I thought this part was useless, but someone else is getting value from it so maybe I should look at it again.”

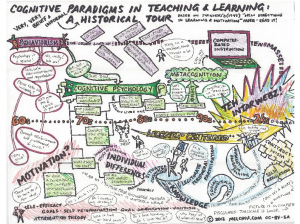

In the landscape of teaching and learning theories -- this is a drawing I made earlier in the semester for one of Robin’s classes...

This puts us in the situated learning camp. We talk about knowledge as being constructed and shared in communities, how knowledge isn’t knowledge unless other people know it too. The two links at the bottom of the slide are an open licensed versions of the big drawing and some written notes that Corey, Farrah, Nick, and I took on this topic in the same class. Notice that because we open-licensed it and put it out there, I can now take this and say “hey folks, if you want to know more, go here.” We wrote it up in class as notes on the side as a whim and now maybe it's useful to people later on.

We end up having interesting cognitive apprenticeships. Participants in these projects get to see how research projects evolve from start to finish, and they also get to see how researchers evolve -- they get to see newcomers learning, more experienced people working with their expertise in that space, and over time they see those newcomers become more and more experienced -- it’s almost like they get to see a little bit of grad school without having to go to grad school, which is a big deal because most of the people we work with aren’t in grad school... maybe they have no time, or they’re not interested, or we hope they’ll go to grad school but they’re from a group that isn’t likely to -- it’s not so much grad school I care about per se, but the sort of deep involvement and critical thought around research that goes on here, and I’m hoping that with RTR projects more people will be able to do that.

This also gets into some thinking about motivation.

Some of you may remember Bandura’s idea of self-efficacy. framework. The second most important factor that makes people believe they can do something is seeing people that look like them do it. So this is letting people see us -- looking like them -- doing engineering education work.

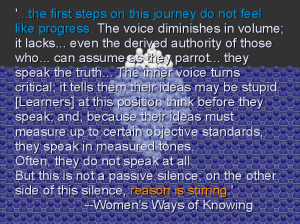

I'm just going to leave this quote up here for a moment. [Reads the quote] This is another iceberg idea. After I talk to people about these ideas, some people say “well that's great Mel, but that's not really necessary. Anyone can find out what I'm doing. Anyone can come up to me and ask for my papers, ask to help with my project, and I'd be more than happy to help them.”

Technically, that’s true. But how many people have actually come up to you and asked? Think back to the days when you applied to this PhD program and didn't know anybody. How much courage and confidence would it take for us to walk up to a strange person and say “You have no idea who I am but I want to help with your research”? How many of us asked that? And we’re privileged and educated and we were already applying to the program. With a lot of people there's an even bigger hesitation barrier there.

And even here at Purdue we complain: “Man, the only way I find out what other people here are doing is when we go to FIE, to ASEE.” We don't find out otherwise. There's no way to eavesdrop. I don't have the time or the opportunity to track down every single person and find out what they're up to. So we don't get to have these kinds of conversations often. If you’re closed by default and opening upon request, it takes a lot of energy to make a request.

If you’re open by default, nobody has to make a request, and because that energy isn't being used to get up the courage to ask, that energy gets used to do interesting things with your project or with your combined project or with their project, or someone else's project, who knows? We don’t know what we’re missing.

That is another quote from women's ways of knowing about lowering the activation energy barrier. [Reads quote]. If we open up the door and say “hey come join us!” instead of “if you want to join us, you must pass through these hurdles before you will be good enough,” it makes a difference. Coming to grad school is a hurdle. Making a login is a hurdle. Reading English, having internet access -- these are all hurdles, and some we can remove more easily than others, but at the very least, don’t put hurdles up if you don’t need to. If you don’t need a login to use the system, don’t require a login just because you want precise data on usage statistics. Do they have to email you? Do they have to be on-site at this time? Why shouldn’t students be able to participate? How can we confirm the largest possible community and tell them they belong here from the get-go?

That's what I had as a talk with the demo and a bit of a philosophical soapbox. I wanted to make sure to leave time for questions. We have about 10 minutes. I know that I have just tumbled a giant ball of beeswax at you. So reactions? Thoughts? Things that stuck out to you?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I was the only one doing the comments. [Laughter] Now I have only 2% battery.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: So you are proposing like a new way for doing qualitative research, right? And maybe new tools to do it. If we want to like disseminate this new way of doing qualitative research why do we still have to stick with the current way of doing qualitative research? Why not propose new ways to do qualitative research? If you think about it, I read an article in a newspaper, say, and I have an argument with somebody about that article, that's somehow qualitative research, right? It's not as you do like here, systematically, but that's still a form of qualitative research. So my question is I think do you think also we maybe have to transform the way we do qualitative research?

MEL: Making sure I have your question right -- do we need to transform the way we do qualitative research so perhaps it encompasses things beyond the conventional procedures I'm going through?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Uh-huh.

MEL: I think that this is a possibility. I think that's a flag that I would love-- if that's something you want to run with, that would be awesome. I don't necessarily think of this as a new way of doing qualitative research. I think of it as a slightly different way of seeing and thinking about sharing the qualitative research we’re already doing and I think one of your insights is that the term the qualitative research we're already doing actually encompasses way more activity than what we would normally put in that box, that dialogue and letters to the editor and newspaper articles and writing something for ASEE or having a Twitter account can count as forms of engagement and research. So we can think of these as well.

Part of the thing I want to point out is that yes, we can make the box bigger, but also that you don't have to move your research outside that existing box. You can use the same procedures you’re already using. Doing RTR does not mean you need to go get a Facebook account. It can mean doing exactly what you're doing the same way you are now but just putting an open license on your data and putting it it somewhere. Or you can get a Twitter account and go crazy. That's also cool.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: So you are putting your data for everyone to be able to take it for their research, right?

MEL: Yes.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: But also the data is very dynamic because people can edit data or add to it, and it's changing all the time. So how do you manage having analysis of the content and the content changing? And how do you control that people are not kind of messing with data, do you know?

MEL: Yeah, so that is an excellent question. My current personal answer to that what I'm doing in my project is I'm setting arbitrary data freezes. We all do this. We all currently do this. We have an arbitrary data freeze at the end of our interview or when we're done transcribing or when we ship a paper for publication. We draw the lines for ourselves and say we're done now moving on to phase two or phase N plus one.

So this is-- I'm pulling up the change makers collaborative transcript... This is an example. There was an interview done and transcribed by other researchers at Cal Poly. We got that and that data was static. It's frozen and done. So only the annotation on top of that data is changing now. Only the comments and notes are changing. If at some point we want to analyze how did we do this process we can freeze our comments in time too and say okay, we're not going to change that any more -- and then we’d have a third layer of annotation. So you can set those boundaries for yourself and say this is going to stop changing now for me. Take a copy. Leave with it and move on.

But what that-- it's interesting to do that because what happens is even if you freeze your copy of the data, other people can keep on evolving their own copies of the data. That's okay. Their copy of the data as it keeps evolving is not going to mess up what you've taken away for yourself. So it lets you have your data set and them have their data set.. Because at some point you do need to draw a line and say “stop changing! I need to graduate!” [Audience laughter]

END OF TRANSCRIPT